Last week, I made a rare trip south of 14th Street to see a double feature of “Where’s Poppa” and “Little Murders” at Film Forum. The minute I spotted this particular program on the Film Forum schedule, I marked it on my calendar in spite of the fact that I own both films on DVD and have seen them countless times. I’ve always considered both films as personal favorites, and among the funniest films I’d ever seen. I wanted to experience them again with a real audience.

Last week, I made a rare trip south of 14th Street to see a double feature of “Where’s Poppa” and “Little Murders” at Film Forum. The minute I spotted this particular program on the Film Forum schedule, I marked it on my calendar in spite of the fact that I own both films on DVD and have seen them countless times. I’ve always considered both films as personal favorites, and among the funniest films I’d ever seen. I wanted to experience them again with a real audience.

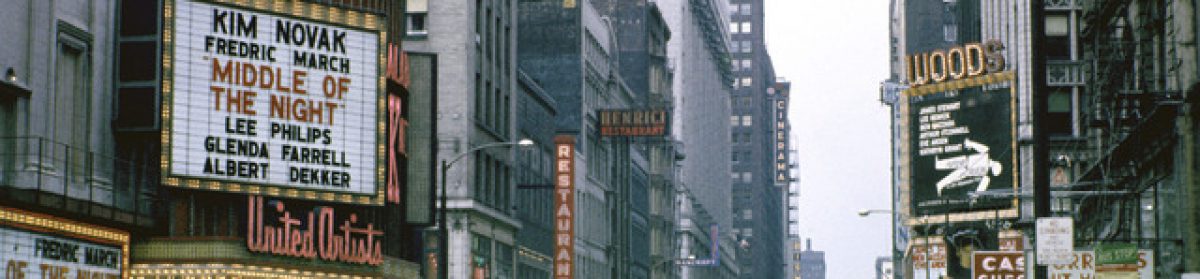

For those of you who are unfamiliar with them, “Where’s Poppa” and “Little Murders” were released a year apart in 1970 and 71. They both take place in the New York of that time, which was at perhaps the city’s least flattering moment. Crime was high. White people were moving to the suburbs in droves, leaving behind a city where the rich folks lived in the fortresses of doorman buildings, and the rest of the city was considered unsafe for anyone. Such are the makings of comedy. Johnny Carson made a nightly habit of joking about just how dangerous it was in “fun city.”

It was also a time when Hollywood was making movies that were pushing the envelope in terms of what was considered tasteful on screen. Writers and directors were given license to be as gross or as un-PC as they wished in the service of a laugh. I was dying to see if the films held up.

I spent the week prior to the showings trying to convince someone to come with me. As I talked the films up, I was shocked at how few people had seen either one. My students at Columbia hadn’t heard of them at all. My wife couldn’t conceive of sitting through two movies. I finally convinced my brother to take the plunge.

At Film Forum, I was thrilled to see that there was a pretty good sized crowd for the early evening show of “Where’s Poppa,” and it likely to get larger for “Little Murders,” since Jules Feiffer was going to introduce the film and do a Q&A afterward.

Would the films hold up?

“Where’s Poppa,” directed by Carl Reiner and starring George Segal and Ruth Gordon was always a strange film. The story of grown man living with his insufferable mother, the film begins with Segal waking up and slowly, methodically carrying out a plan to scare his mother (literally) to death by jumping on her bed in a gorilla suit. That’s just the beginning. Over the course of the film, Mama does everything she can to make her son miserable, including undermining his relationship with a potential new girlfriend.

Unfortunately what used to play as one of the funniest films I’d ever seen was now falling flat. A few of the big laughs in the film still work, but a lot of them no longer do. The acting is so broad that it’s hard to believe that it ever worked. In particular, Ruth Gordon’s performance is so over the top, that it’s painful rather than funny. Some of George Segal’s reaction shots are interminable. I’m always warning film students to make sure that their actors play their parts straight in comedies. Actors who are asking for laughs are simply not funny. Somehow Carl Reiner missed that lesson, and the film comes across as a bad Saturday Night Live sketch. The only actor whose performance still works is Ron Liebman, who plays George Segal’s guilt-ridden brother. His manic, sweaty performance nails a type that rings even truer now than it did in my earlier viewings.

One other problem with the film is a function of how times have changed. The film satirizes racial stereotypes in such a direct manner as to make it uncomfortable. Ron Liebman’s character gets mugged every night by the same black muggers in Central Park. Reiner trots out every black stereotype n the book, and what seemed outrageously funny in 1970 is now very hard to watch. On the other hand, Reiner gives us one of the greatest sight gags about racism in the history of the movies–one that is so quick and offhanded that a lot of the audience missed the joke. A taxicab is about to pick up an older black woman, but it passes her up to pick up a guy in a gorilla suit. Still hilarious.

The final disappointment was that Film Forum was showing a print that included an unreleased ending. The original version ended with the biggest laugh in the film, and on a note that was both sweet and very satisfying. The new ending keeps going for another 3 or 4 more minutes and ruins everything that came before. I’m told that this alternate ending is on the DVD as an extra, and that is where it belongs. It completely ruins the movie.

“Little Murders,” as it turns out, is a completely different story. The movie holds up in every way.

The film was written originally as a play by Jules Feiffer, and was initially a flop. A couple of years later, it was revived by Alan Arkin, who directed it at Circle in the Square. The play, with Elliot Gould in the lead role, became a cult hit. After the release of “Mash,” Gould had become a big star, and was able to use his status to get the film version financed with Arkin directing. Gould recruited his co-star from “Mash,’ Donald Sutherland, but the rest of the cast was from the play–a collection of some of the great New York character actors of that time.

Gould plays a photographer who has become so disillusioned, he only takes pictures of shit. He meets a perky woman who decides to “save” him. The movie follows their relationship and becomes a psychological war between them. Will she convert him into an optimist or will the world conspire to make her see everything as shit. We meet her bizarrely dysfunctional family and a parade of desperate, angry New York types who convincingly test any notion that there is anything worthwhile left in the world. As the movie barrels forward, it get crazier and crazier until it explodes into some surreal dystopian vision of a city gone nuts.

Beat for beat, word for word, the film is bold, brilliant, hilarious and in your face. It features a number of long monologues that in lesser hands would stop the movie dead. But it works because the writing and the acting are so strong. There is one scene where Gould tells a story that lasts over four minutes without any cuts. It’s mesmerizing, poignant and the acting is brilliant. Similar virtuouso scenes are performed by Lou Jacoby, Vincent Gardenia, Donald Sutherland and Alan Arkin. Arkin’s scene is so manic that you can actually see him trying to keep himself from breaking out laughing, but he keeps it just enough in check to make it work.

In the Q&A after the film Feiffer explained that the inspiration for the original play was trying to make some sense of the Kennedy assassination. I can only say that post 9/11, this film should be required viewing. It’s as relevant as ever. And unlike “Where’s Poppa,” has stood the test of time–the true definition of a classic.