There isn’t a day that goes by when I don’t read The New York Times. I fully admit to being one of those old-fashioned people who reads the news on paper; I flip through every page, skimming the articles, diving into whatever grabs my attention, and feeling like I’ve absorbed enough information to be up to date on our crazy world.

There isn’t a day that goes by when I don’t read The New York Times. I fully admit to being one of those old-fashioned people who reads the news on paper; I flip through every page, skimming the articles, diving into whatever grabs my attention, and feeling like I’ve absorbed enough information to be up to date on our crazy world.

There also isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t get pissed off at The Times for one reason or another. The insistence on presenting “both sides” of every issue, to the point of false equivalencies, is a particular source of anger. (Let’s not forget that it was The Times that broke the story of “Hillary’s emails” and continued to hammer it all the way to November.)

However, all told, The Times does a better job than most daily newspapers of at least trying to get things right. And in an environment in which newspapers around the world are under severe threat of extinction, I find it heartening That they have found a way to keep the paper alive while deftly navigating new business models to support it.

That said, what brings me to write comes less from my personal and political perspectives as a reader than my professional perspective as someone who lives in the world of movie marketing; more specifically someone who has spent their life trying to get audiences to see less commercial fare in movie theaters. The Times has always played an important role in that effort, but unfortunately in recent years, changes have been made that have created great obstacles to that effort.

I know that folks living in other cities will look at The Times film coverage and wonder what I’m complaining about. After all, The Times is one of the few remaining daily newspapers with any extensive film coverage. As Greg Laemmle recently wrote, the Los Angeles Times (of all places) has literally NO film reviews anymore. This is also true in most other parts of the country. So, what’s my complaint about The New York Times? As a national publication that fancies itself an arbiter of culture, it has the opportunity, and one might say the responsibility, to fill that void.

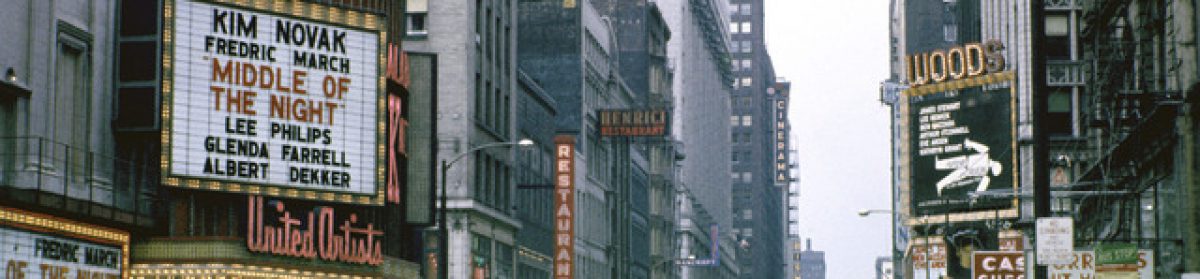

Daily newspapers used to be the lifeblood of movie promotion both large and small. In almost every city, the daily paper was the main source of information about what was playing, in which theaters, and at what times. This came from a combination of directory listings and display advertising. There were a range of ad sizes to suit big budgets by making a splash and smaller budgets by being strategic. All this advertising was surrounded by extensive editorial coverage that included reviews; interviews with actors, directors and others; and specialized coverage that was pitched to the local papers by local publicists with angles that were unique to each individual film. Additionally, almost every major city newspaper had its own local critics, who (in theory) were attuned to the tastes and standards of their individual communities. Many of these critics took on the responsibility of pointing their readers to films that they might have otherwise overlooked. This was in no small part the reason that so many offbeat films broke through to national audiences.

This combination of advertising and editorial, side-by-side, was the perfect environment for anyone interested in film, or anyone simply interested in going to the movies, to size up what was out there and to make a decision about which films they wanted to see, and where and when they could see them. For all practical intents and purposes, it was the point-of-purchase.

Many things have changed since this was case.

The major studios shifted most of their advertising to television and later to digital, severely cutting back on newspaper ads in all but the largest cities. Classified ads moved to Craigslist. As local newspapers lost advertising revenue, they found their income models to be unsustainable. Meanwhile circulation was dropping as younger readers moved to the web. Cutbacks became necessary to stay alive. Among the first casualties were local arts reporters and film critics. Across the country, most local newspapers began to get their arts coverage from national wire services (increasing the importance of those few publications that continued producing their own editorial coverage.) Circulation numbers were reduced to a fraction of what they had been; mainly comprised of an older demographic—not exactly the most coveted audience for advertisers. In effect, the virtuous circle of editorial and advertising that had created the perfect point-of-purchase for moviegoing was being dismantled brick by brick.

So where does The New York Times fit in?

Even in the days when local newspapers reigned supreme, The Times had inordinate power and influence. As the media capital, New York was where films were launched, and the critics at The Times were uniquely charged with finding a middle ground, speaking to both lovers of big Hollywood movies and smaller, more specialized and artier movies. The paper had a history of dismissing much of the big stuff and championing the more ambitious and the more challenging. The policy was that every film that opened in theaters in New York for at least a two-week run would get reviewed in the paper. In the early days, those reviews would run the day after the film opened. In later years, it became the day the film opened. This commitment went far beyond any other publication.

The prestige of The Times reviews made them both coveted and feared. Distributors would try to game the system by choosing the day of the week that a film would open. Expect good reviews? Open on a Friday so the review would be featured in the Weekend Section, and potentially propel opening weekend business. Have a smaller film that may get lost in the sea of Friday reviews? Open on a Wednesday when there are fewer films competing for space. If the review is good, you can grab a quote for your Friday ads. If the review is bad, you can bulk up your Friday ads with quotes from other publications. Not sure about the reviews? Open on a Sunday, when any reviews will appear in a section other than “Arts & Leisure” (which prints earlier). Expect bad reviews? Open on a Friday, but without screening for press. In that case, the Times would send its critics to see the film in a theater and the review would appear in the Saturday paper, which is the day with the lowest circulation. Get the idea?

Advertising was also a game. While the studios could afford to advertise all week, smaller films had to strategize about how best to allocate their dollars. A large ad on the Sunday before opening could make a film seem bigger and more important, both in New York and around the country, since the Sunday Times had a larger circulation outside of New York than the daily editions.

The New York Times (as well as the Los Angeles Times) also had outsized influence because so many Academy members live and work in New York or Los Angeles. This attracted advertising dollars that helped support the paper through the digital transition, and still does to some extent.

This all added up to an enormous amount of influence, which has only increased as other local newspapers abandoned the space. This has also given The Times an enormous amount of responsibility whether they like it or not.

Unfortunately, all of this is being squandered through a steady chipping away of some of what made The Times movie coverage special. At a moment when theatrical moviegoing is under stress, The Times is uniquely positioned to set the tone for cinema’s revival. Trying to weigh the challenges of surviving as a daily newspaper with the needs of the current theatrical marketplace, I have come up with a seven-point plan for how The Times can adapt its policies to serve theatrical moviegoing and its own revenues.

1. Movies are in theaters…TV Movies are on TV.

In a typical week, anywhere between 15-20 new movies are reviewed in the paper. Right now, the way these reviews are organized is completely unhelpful to potential audiences. There is longstanding research indicating that on any given night, consumers first decide whether they are going out or whether they are staying home, and then choose among in-home or out-of-home activities. At this moment, The Times organizes it reviews under the headings, “Movies” or “Television,” which is misleading and confusing since at least a third of the “movies” being reviewed are only available in the home. It would be more helpful to have a section clearly labeled “In Theaters” and another called “Streaming.” In this way, people who are thinking about going out to the movies don’t have to read the fine print to see which ones might be available in theaters. Any film that is also available on streaming services can still be in the “In Theaters” section if they actually are. And the fine print can let people know that this is the case. This will not only help potential audiences sort things out but might also influence the actual release patterns of the films in question. So long as streaming movies are listed side-by-side with theatrical movies, without any differentiation, distributors are able to use the confusion to create completely misguided release strategies. Movies that are premiering on Netflix are TV movies. TV movies are and have always been “television.”

2. Reviews of a film should be released on the day of its first availability to audiences, no matter where it plays.

A movie that premieres on Netflix should be reviewed on the day it is available on their service. A movie that is released in theaters should be reviewed on the date of first theatrical release. If a film is platformed out of New York, which most art films are, it should be reviewed when it opens in New York. This not only supports the first week of box office, which is crucial to getting bookings in the rest of the country, but it also serves to tease audiences outside of New York that the film is coming. It also forces distributors to make a decision about whether a film is theatrical or not.

3. Reviews should be released on the website on the same day they appear in print.

The drip, drip, drip of having reviews appear whenever they become available removes the sense of an event, which is what drives people to theaters. Make people anticipate them. Create a sense of urgency. Release all the reviews at midnight on the day they are released. As far as streaming movies are concerned, the date is less crucial. For the most part, those movies will continue to be available for a long period of time.

4. The presentation of reviews on The Times website needs an overhaul.

Right now, if you want to see a movie and use The Times site as a guide, you must drill down from the main page to “Arts” to “Movies” to “Movie Reviews,” and then you get a list of titles and links in the order of most recently reviewed. The content of that page needs to be more like the print edition. It should be headlined something like “New in Theaters This Week” and, at the very least, contain the first paragraph of each review, basic credits (director, stars and distributor), running time, rating and a photo. If you click on one, it should expand to show the full review, along with a link to buy tickets. After the first week, those reviews should be moved to a secondary page, called “Still in Theaters,” where they would stay for as long as the film remains in theatrical release. Once the film is no longer in theaters, the review should be moved to the “Now Streaming” page or removed entirely. I understand that ticketing links are complicated, but the current use of the IMDB page serves no purpose as most films come up empty when you click the link. Maybe there’s a way to make distributors pay a fee to have a link to their own web sites, which they would be incentivized to keep up to date.

5. Give more space to the freelance critics, when deserved.

The Times’ lead critics, A.O. Scott and Manohla Dargis are brilliant reviewers—incisive and fun to read. As with any good critic, you will not always agree with their opinions. But if you read them regularly, you can get a pretty good idea of what their tastes and prejudices are, and even why they may have been assigned to particular films. In the meantime, the vast majority of films are reviewed by others, who I assume are freelancers. I know enough about some of these folks to know that many of them are very capable as well, and I would like to see them given more space so that the reviews are something more than book reports. Yes, there are a lot of movies that deserve to be dismissed in three paragraphs (or less), but when one of these freelancers comes across a film that is worthwhile, they should be given the wherewithal to devote the amount of space that the film deserves. In a mostly web-based world, there is no limitation on the space available, as there is in the physical paper, so the only limitation I can think of is that The Times is paying by the word. Maybe this isn’t true, but it sure seems like it is. Open that up and you increase the value of more of the reviews. Do that and it begins to resemble the environment that would attract more advertising.

6. Create a NYT movie app.

It is probably inevitable that the print edition of the paper will eventually disappear. This is a shame not only because old habits die hard, but also because, as I have written previously, when it comes to digesting the news, the medium is indeed the message. The experience of turning the pages of a print publication encourages exposure to topics that one might never seek out in an environment that is driven by clicks. In my opinion, this is the source of some of the polarization that is going on in our country. It is also a huge problem in terms of exposing potential audiences to a range of movie choices. That perfect environment of side-by-side editorial coverage and advertising that enabled audiences to browse available offerings in a compelling and entertaining fashion has yet to be duplicated in any digital format. I would like to see The Times work harder to recreate that experience on the web, and perhaps more importantly, develop an app—let’s call it “The Movie Pages”—where users can swipe through a feed that includes the reviews of the films opening that week, ads that are bought by distributors, directory ads from theaters that are localized to the user, and feature articles. The app should be designed so that all editorial content is presented in its entirety, rather than as links, so it can be skimmed through. Ads should be available in multiple sizes so distributors would have various price points to choose from. Directory ads should be priced according to what city they appear in, and how many days of the week they appear in the app.

7. Create a new nationally syndicated weekly movie section

While it may be true that print is dying, it still draws a substantial older audience–the very audience that has traditionally supported art films. The Times should not only not abandon this audience, it should take advantage of the vacuum elsewhere. When I worked for Ted Turner, one lesson I came away with was that a successful media company finds ways of creating new outlets that repurpose content that is already being created. Perhaps The Times could create a special weekly section—it could also be called “The Movie Pages” just like the app proposed above. It could be tabloid size, just like the Book Review section. It would include all of the elements in the app I’ve described above, from the reviews to the ads to the directories. In addition to tucking that section into the Friday or Sunday papers, offer it up to other local newspapers around the country in the way that Parade Magazine used to be bundled nationally. Come up with a model in which those papers have one page to sell locally, which becomes their revenue stream and can include local theater information. In the meantime, The Times benefits from a larger circulation to sell to national movie advertisers. The special section could also be distributed at the theaters themselves.

I realize that most of this is a pipedream. Some would characterize it as hairbrained or retrograde or just plain naive. I’m sure the folks who run The New York Times will have a million practical reasons why things are the way they are, and why these ideas are not viable. But at the very least, I hope they see this and think hard about their role in the future of the theatrical business, especially of smaller, more specialized films. The self-proclaimed “newspaper of record,” which to some extent has always been depended upon to be an equal opportunity voice to promote the art of cinema and to highlight those films that deserved attention in spite of their modest budgets or off-beat origins, is needed now more than ever.

Ira: This is a very well thought out argument and an opportunity (for you) to create a better platform on social media or as an app to review and promote theatrical and streaming movies. If the NYT isn’t savvy enough to step up, well then . . .

Wow! I hope that this is not a pipe dream but rather a playbook for the Times or someone else to follow to reenergize and possibly save the movie world, in particular the independent film world. It saddens me to see what is happening to a part of life that I love. Covid worsened the situation but it was badly wounded long before. Thank you Ira for your insight and thoughtful recommendations which if taken even in part will make a difference.

Good work

So well thought out Ira. I hope the Times or someone takes it to heart.