A few days ago, I announced the long-awaited release of my film “Searching for Mr. Rugoff” (long-awaited by me, anyway). It’s been a protracted journey with many twists. I’ve begun to reflect on the many decisions I made along the way–fortunate and not–and thought some of it might be instructive for others (the teacher comes out in me!)

A few days ago, I announced the long-awaited release of my film “Searching for Mr. Rugoff” (long-awaited by me, anyway). It’s been a protracted journey with many twists. I’ve begun to reflect on the many decisions I made along the way–fortunate and not–and thought some of it might be instructive for others (the teacher comes out in me!)

The project itself was years in the making, and at many points I wondered if it would ever actually add up to anything. I was once told that narrative features are a sprint, but that documentaries are a marathon. Trite but true. There were many times when I thought the film was as good as it could be, only to get feedback that made me take yet another look, leading to yet another version. The process was often frustrating and infuriating, but with each iteration, it seemed to get better. I had work-in-progress screenings for the students at Columbia, at the offices of Kartemquin Films in Chicago, at the Michigan Theater in Ann Arbor, and at the 2019 Art House Convergence. And while audience reactions were very encouraging, I always walked away with more notes—sometimes completely contradictory.

Yet… it was after that last screening that I had a revelation. There was a section of the film that was clearly slowing down the pace, but it was a section that I resisted cutting out. It was just too important to me. It dawned on me that if I moved that section to a later part of the film, perhaps it would work better. The running time was exactly the same, but the pacing issue seemed to be gone. The change was transformative. More eyes on the film convinced me the film was finally done.

Now I had to race to get the film ready for its scheduled premiere at Doc NYC. It’s worth mentioning that having the world premiere of the film at Doc NYC was a controversial decision. Friends and colleagues were advising me to hold out for the possibility of Sundance or Cannes Classics—festivals that had more of a track record of sales to distributors and major press coverage—but I liked the idea of Doc NYC for several reasons. First, I was anxious to get things started and loath to stall any longer. Second, the film was at least partly about the New York film scene and would hopefully resonate more deeply here than anywhere else. Third, I knew I could draw a hometown crowd that would make the screenings special. Finally, because it wasn’t one of the top-tier film business festivals, I thought I could make the film stand out.

The premiere was in front of a packed house at the IFC Center and exceeded even my wildest expectations. The audience laughed and cried. The Q&A was a love fest. Many of the people who are in the film were able to attend, and the party afterward was a reunion of folks who in many cases had not seen each other in 40 years. The next day, the film was favorably reviewed in trade papers and local blogs. In fact, it appeared to have gotten the most press coverage of any film in the festival; I was elated.

Distributors who had been at the screening told me they loved the film, but were dubious; would it resonate with anyone other than people in the film business? They wanted their colleagues to see it. I was fine with that reaction, since I was convinced that the momentum would continue to build, and that would, hopefully, eventually, change their minds.

Other festivals started making offers to show the film. The Palm Springs Int’l Film Festival would be the west coast premiere, followed by festivals in Cleveland, Madison, Chicago, San Diego, DC, and Ann Arbor. The international premiere was in the works but not yet settled. The momentum was indeed building.

I had just returned from the Palm Springs festival in January 2020 when I first started to hear about that virus in China. During a faculty meeting at Columbia, we were given a quick overview of what might happen if we had to go to remote teaching for some period of time. Our collective reaction was, “huh?” The virus had yet to be found anywhere in the U.S.

You know what happened next. There were way more serious matters to be dealt with than the fate of my little documentary. But the question of what would happen to it was always in the back of my mind.

One by one, the festivals either cancelled or went virtual. Would virtual festivals kill my chances with other festivals down the road? Festivals were certain to come back within a matter of weeks, right? Uh, maybe a few more months? Dire predictions of the end of the movie business were being printed everywhere. This made no sense to me. I’ve been teaching for decades about how many times the theatrical film business has been threatened with certain death, only to survive and thrive.

Whether this turned out to be a temporary crisis or a permanent change in the culture was of no consequence at this particular moment. The issue was near-term survival. Theaters were closed. People were losing their jobs. Larger distributors were postponing their biggest releases and dumping their smaller ones. The smaller indie companies were trying to adapt. Films acquired for theatrical release were sold to streamers. Horror movies for drive-ins? Why not. And then an intriguing concept was developed called “Virtual Cinema,” in which local theaters, closed to physical audiences, could share in the revenues of on-line screenings by marketing them to their patron lists. This would help support those theaters, but also keep their audiences engaged.

I became obsessed with the “virtual cinema” model and researched it to death. I contacted and interviewed all the available platforms and many of the participating theaters and distributors. I wrote several articles on the subject exploring what was being done, right and wrong, and whether there was a future for this business model. My public speculations led to invitations to be on panels and to lead discussions on the subject. But what I was really doing was trying to figure out what to do with my own film.

Whatever momentum my film may have gained from its festival launch was certainly no longer a factor. It made no sense to try and create any noise when it was unclear when the film could ever be shown in theaters again. I had nothing against showing the film “virtually,” except that the film is at least partially about the theatrical experience–something that I didn’t want to squander.

Then, one day in June of 2020, I got a phone call from David Schwartz, who had recently been hired by Netflix to book films into the legendary Paris Theater in Manhattan. David had been at that first screening at Doc NYC and had witnessed first-hand how well the film played for a general, non-industry audience. David also knew that Don Rugoff, the subject of the film, had booked and managed the Paris Theater for two decades in the 60’s and ‘70s. He decided he wanted to play the film as part of the re-opening of the Paris, whenever and however that would eventually occur. At that moment, I knew that as frustrating as it might be, I had to wait for that opportunity. It was just about the best way I could imagine to re-launch the film.

I also began thinking about what else might be done, and realized I would just have to take the bull by the horns and release the damn thing myself. It’s not as if I didn’t know how to do it. I was a distributor long before becoming an educator, producer and, most recently, a director. But I know from experience that distributing a film is not to be taken lightly. “Getting butts in seats,” as they say, “is really hard.” So I tried to channel Don Rugoff, who understood that you need to have a hook to get attention. I decided to tie together my urge to see the film play in theaters, which is where I believe it belongs, to a plan that might help indie theaters in their moment of need. I decided to make the entire release a benefit for the re-opening of art houses nationwide.

Throughout the pandemic, speculation about the future of the film business was a popular subject of pundits, right up there with “will workers ever return to offices?” It went from temporary closures to existential threat to wait and see. Now, every weekend’s box office provides the latest version of the tea leaves that will somehow predict the future of the business. The most common conclusion (as of today) is that audiences will only return to theaters to see big blockbusters that demand to be seen on the big screen, but that the art film business is in big trouble.

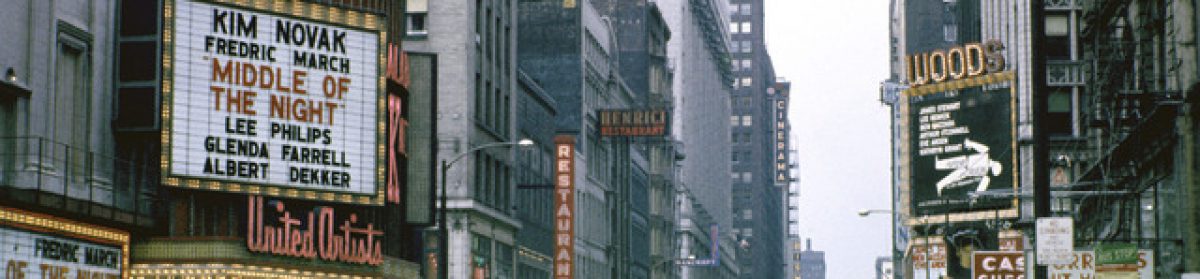

Back in the 50’s and ‘60s, there was a similar dynamic at play; conventional wisdom was that this new invention called television was going to put movie theaters out of business. The big studios thought the solution was putting all their resources into huge blockbuster films. Don Rugoff and others had a different solution that changed the course of movie history, which was to offer something bold, different and original, and to market it aggressively and imaginatively. I hope my movie can inspire the film business and the audiences they crave to start thinking that way again.