I don’t usually write reviews of films I’ve seen, but after a public debate (on Facebook) with my son, I feel compelled to explain my feelings about the new Woody Allen film in a larger than Twitter-sized forum.

I don’t usually write reviews of films I’ve seen, but after a public debate (on Facebook) with my son, I feel compelled to explain my feelings about the new Woody Allen film in a larger than Twitter-sized forum.

In the context of Woody’s career, it would be easy to dismiss “Whatever Works” as a minor piece. The plot makes very little sense, the characters are all “types,” and the world the film takes place in is as realistic as Seinfeld’s apartment building.

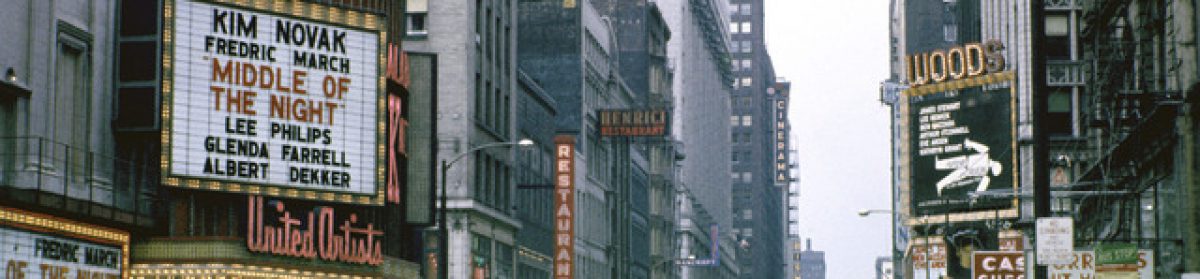

But that’s the point. Woody is just having fun. From the moment the fourth wall is broken in the first few minutes of the film, you know that we not meant to take the film seriously. But the big moment for me is the first time there’s a knock at the door and an unexpected guest enters. Does anyone know anyone who lives in NYC who doesn’t have a doorbell, or intercom, or at least a peephole they would use before opening the door? As cloistered as Woody’s life has been, even he would know that…or if not, someone on the set would have pointed it out. The “knock on the door” is is one of the oldest devices of pure farce. The apartment where a large part of the film takes place might as well be the set for a play, tailor made for unexpected entrances and exits. The New York portrayed in this film is about as real as the Russia portrayed in “Love and Death.” It’s all about the gag.

Not every joke in the film works, but this is some of the densest comic writing that Woody has done in a long time. And he still knows how to wring a punch line out to maximum effect. Bottom line is I laughed more than I have at a movie in a long time.

One final point. Even though every character in the film is portrayed with heightened ugliness–each one is stupider, cruder and/or more horrifying than the next–the movie actually leads to very sweet, if simplistic place. Happiness in life and love is mostly found in unexpected places–that’s what the movie (and the title) is saying. While this could (and will) be read by some to be yet another rationalization of Woody’s own life choices, it seemed to me to be coming from a more genuine place. I’ve always been a sucker for that kind of sentiment. I just never thought I’d see it in a Woody Allen film.

Happy to continue the discussion here.

Woody has always expressed his misanthropy in his films, often to good effect, but never as explicitly as in “Whatever Works.” In this film, it is as explicit as a direct address, which I read less as playfulness than as lecture – to the audience and also to the female lead, who finally literalizes the function that women have often performed in his films: student.

In “Annie Hall,” it seemed as though Woody was aware of his own hypocrisy when Alvy encourages Annie to take adult education classes so she can qualify as his intellectual equal. In “Manhattan,” Isaac understands that his relationship with Tracy, a 17-year-old Dalton student, is an unserious fling and wisely ends it before she can naively invest too much. When he tries to get her back at the end of the film, we understand that he is being impetuous and selfish. In “Whatever Works,” Boris first turns down Melodie’s advance with just the kind of realistic, self-consciousness you’d expect of a Woody Allen character. But when he later convinces himself that they are meant to be together, he mistakes the teacher-student relationship for romantic destiny, and there is little sense here that Woody is aware that this is a misstep, as he seems to be using it as a rationalization of his biography.

The irony of this film is that it is both the most didactic example of Woody’s misanthropy and a misguided rejection of it. The ways that characters fall in love resemble the kind of inane “Sliding Doors”-isms that Woody has made a career of demystifying. Some of the film’s gags – most notably the one about the homophobic southerner who, whadayaknow, turns out to be gay – actually feel as though pulled out of one of the litany of Woody Allen-lite films made in the 90s (see Ed Burns et al).

Finally, the “Whatever Works” mantra that guides this film is not enough to rationalize the lack of perceptive comedy and ethicality. I can just imagine what Woody of the ’70s might have said of the phrase: “whatever works, as long as it’s not working for Nazis.” Because the obvious problem is that whatever might work for Woody these days doesn’t necessarily work for his love interests or his audience. And from what I know of the way he works, I sort of doubt he’s listening to anyone on the set.

I agree that Boris is the most overt expression of misanthropy in Woody’s work to date, but I read it a little differently. Having Larry David play the role, rather than Woody himself, removes the cute nebishy side of the character, and doesn’t ask us for any sympathy. Even though Boris keeps insisting that he’s a genius, and knows everything better than everyone, ironically it is actually Melodie who turns out to be wise. The best moments in the film (other than the laughs) are when Boris realizes this. By the time he faces the audience at the end and declares his genius one last time, it feels to me like he’s acknowledging that he’s actually not.

Anyway, I don’t love the film enough to keep at this. But this is fun. We should do it more often. Maybe they need replacements at the Ebert & Roeper show.