Within a month of when I started working at Cinema 5 in 1975, Joan Micklin Silver’s first feature, Hester Street, opened at the Plaza Theater on 58th Street. The Plaza was one of the Cinema 5 theaters and it was located around the corner from our offices. Every night, on the way home from work, I would see the lines of people stretched all the way down the block toward Park Avenue. The film was a huge hit. Around that time, I first met Joan and her husband Ray when they came to our offices to make a deal with us to distribute the film to the non-theatrical market. I learned that my boss, Don Rugoff, had turned the film down for theatrical distribution because he thought (as many others did) that the film was “too niche.” But now that the film was a hit, he wanted in.

Within a month of when I started working at Cinema 5 in 1975, Joan Micklin Silver’s first feature, Hester Street, opened at the Plaza Theater on 58th Street. The Plaza was one of the Cinema 5 theaters and it was located around the corner from our offices. Every night, on the way home from work, I would see the lines of people stretched all the way down the block toward Park Avenue. The film was a huge hit. Around that time, I first met Joan and her husband Ray when they came to our offices to make a deal with us to distribute the film to the non-theatrical market. I learned that my boss, Don Rugoff, had turned the film down for theatrical distribution because he thought (as many others did) that the film was “too niche.” But now that the film was a hit, he wanted in.

My job at the time was as a non-theatrical salesperson, so I was on the phone all day with colleges, libraries and other organizations, trying to get them to book our library of films. Hester Street would not only be a valuable addition, but would be of particular appeal to Jewish organizations, which we were already servicing with such films as Garden of the Finzi-Continis and The Sorrow and the Pity, among others.

As part of our marketing efforts, I started to have interaction with Joan and Ray. Their office was right across Madison Avenue from ours, and I would go over to pick up whatever we might be able to use to create our promotional materials. The more I learned about the history of Hester Street—how it was financed, how it was produced, how it was being distributed–the more Joan and Ray became heroes to me. As a young, ambitious person who wanted to be in the film business, I saw in this power couple a force that refused to hear the word “no.” When Joan first tried to set the movie up with the major studios and was met with blatant sexism, Ray rounded up his real estate buddies and raised the financing to make the film independently. When the finished film was regarded as too small–even by independent distributors–Ray created his own distribution company to handle it. Now the film was a certifiable hit at the box office and an Academy Award nominee to boot.

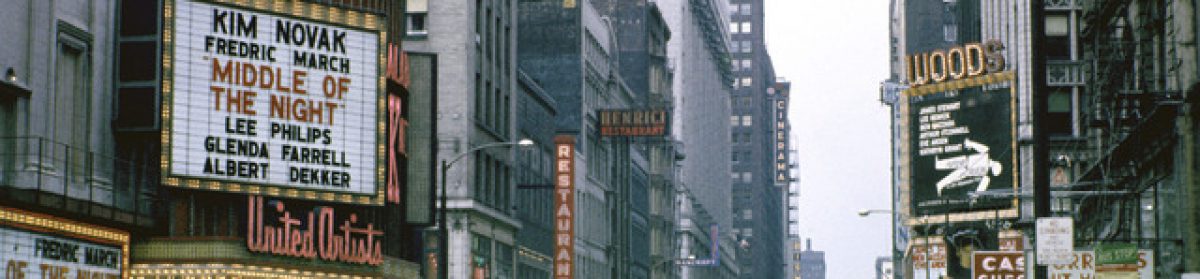

Over the next couple of years, I was among the first in line to see each of Joan’s new films as they came out. I loved Between the Lines (which, by the way, really holds up). Joan’s next film was made for a major studio, United Artists. It was released under the title of Head Over Heels, and even though it was considered a flop, I loved it. What I didn’t know was that this film would become my second encounter with Joan.

In 1980, I ended up getting a job at United Artists Classics, and one of our activities was to take films from the UA library and try to squeeze additional profits out of them. We had just had a somewhat triumphant re-release of a UA flop called Cutter and Bone, which we retitled Cutter’s Way. It was then that we were approached by the producers of Head Over Heels— Griffin Dunne, Mark Metcalf and Amy Robinson–with the idea to do the same with their film. The film had been based on the book Chilly Scenes of Winter, and they advocated that we change the film title back to the original to better reflect the intended tone. The producers also told us that UA had insisted on adding a “happy ending” to the film, which they wanted to remove. When I screened the proposed version of the film, I loved it even more, and was thrilled to have a role in resurrecting the film and getting it to a much larger audience.

From that moment forward, I was never out of touch with Joan and Ray, as our paths intermittently crossed over the decades. We would see each other at social events and screenings, and I would get calls from them for advice or feedback on projects they were working on. Over those years, I still went to see all of their movies. I say “their” because not only did Ray continue to produce films that Joan would direct, but Joan produced films that Ray would direct. And the whole family collaborated on a film that was directed by their daughter Marisa.

In later years, my wife and I were lucky enough to become among the people who were invited to Joan and Ray’s home for the wonderful dinner parties they would throw, which not only gave us the opportunity to get to know them and their daughters even better, but we were lucky to be introduced to a cast of notable critics, actors, authors and others who were all long-time close friends. The dinners were always delicious and the conversations even more so.

We were shocked, in 2013, when we heard that Ray had died in a ski accident. Joan was devastated.

Since Ray had handled all of the couple’s business dealings, Joan turned to me to help out with some loose ends, which I was more than pleased to do. After scouring through the paperwork on the Silver family film library, I ended up selling the distribution rights to Cohen Media Group, which is currently in the process of restoring and reissuing the films. And in an amazing bookend to how my relationship with Joan and Ray began, I ended up in a partnership to adapt Hester Street for the stage. The idea had been brought to Joan by a young theater producer, Michael Rabinowitz, who saw something in the story that resonated with the issues of today, and now he and I are working with an amazing creative team to get it done. One of my happiest moments was last year when Joan came to see a staged reading of the adaptation and expressed how pleased she was. (By the way, she had some very sharp and astute notes for us.)

It’s incredibly sad that Joan didn’t live long enough to see her films revived in movie theaters, which will be happening over the next few years. I also wish she could have lived long enough to see Hester Street open on Broadway. But I feel grateful that I got to know her and spend time with her, and that she and Ray became part of my life. I’m also grateful that she is being recognized for the important, groundbreaking artist she was. Joan’s body of work is a vital part of the history of independent film. And Ray doesn’t get enough credit for virtually inventing the use of limited partnerships to finance independent films–the structure that has become the de facto standard in the industry. In a small way, their partnership was a big “fuck you” to the major studios and the limitations they impose on the diversity of cinema. They were an inspiration to so many.

Here is a Q&A after a screening of Hester Street a few years ago…